Ethics of AI in Education Collective Reflections from the Italian Awareness Raising Session

By Juliana Raffaghelli, Francesca Crudele, Martina Zanchin

🇮🇹 Versione italiana: leggi qui

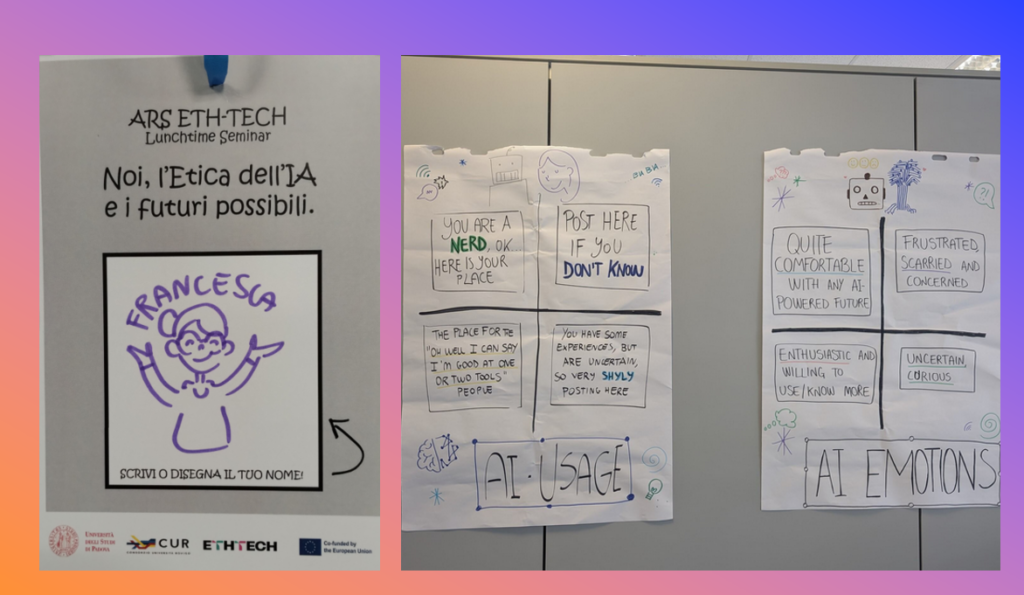

The “ARS” or “Awareness Raising Sessions” are part of a participatory strategy to focus on aspects of AI Ethics that will then become a key element of the Open Educational Resources within our project (see Activities).

In this post, we tell you about how the session held at our UNIPD university campus in Rovigo went, which gave us wonderful hospitality!

We shaped our meeting as a “Lunchtime Seminar”: sharing lunch and sharing ideas, to nourish ourselves 😉

Session Overview

The session began with participants working in small groups on fictional but realistic ethical dilemmas related to AI use in education. Despite being offered ten different cases—ranging from domestic use of Alexa, to school surveillance, to institutional governance—multiple groups coincidentally selected the same one: a university computer science class where students used AI collaboratively, without resistance or guidance from their professor. The case sparked immediate recognition and identification.

“We actually found that we live a similar situation,” one participant shared. “As students, when we’re given group tasks, we organize, we use AI, because it’s available. So you use it.”

What began as a reflection on a single classroom example soon unfolded into a broader collective inquiry into what it means to teach, learn, and act ethically in increasingly digitized and datafied institutions.

“It’s like a simulation”: Teaching and Learning on Autopilot

At the heart of the case was a sense of disconnection—between students and teachers, between intentions and actions. One participant described the dynamic in stark terms:

“The teacher was literally indifferent. He didn’t care that students used AI and didn’t think critically on their own… He just wanted to secure his job.”

The situation resonated widely. Another participant offered a chilling metaphor:

“It’s like a simulation of the educational environment. The students are simulating learning, and the teacher is simulating teaching. Everyone is just playing along.”

This idea of “simulation” echoed Gert Biesta’s critique of performative education: systems driven more by appearance and compliance than by purpose and meaning. The passivity of the teacher, paired with the tactical pragmatism of the students, exposed how AI was being quietly normalized—not as an object of inquiry, but as a background tool in a broader educational performance.

“You feel guilty, but you still use it”: Emotional Ambivalence and Ethical Drift

The conversation moved into the emotional terrain of the issue—what it feels like to use AI in these ambiguous spaces. A student participant reflected:

“We talked about emotions—feelings of guilt, disappointment, bitterness… that Italian word amarezza. You know it’s not really right to use it, but you do it anyway.”

Others spoke about the emotional burden teachers carry:

“They’re overwhelmed. There’s the program to follow, society’s expectations, institutional deadlines… and maybe also this fear of being replaced by AI.”

Such reflections revealed a profound emotional complexity: students caught between capability and conscience; teachers torn between care and exhaustion. The session made clear that AI ethics isn’t just about abstract principles—it’s saturated with affect, anxiety, and tacit compromise.

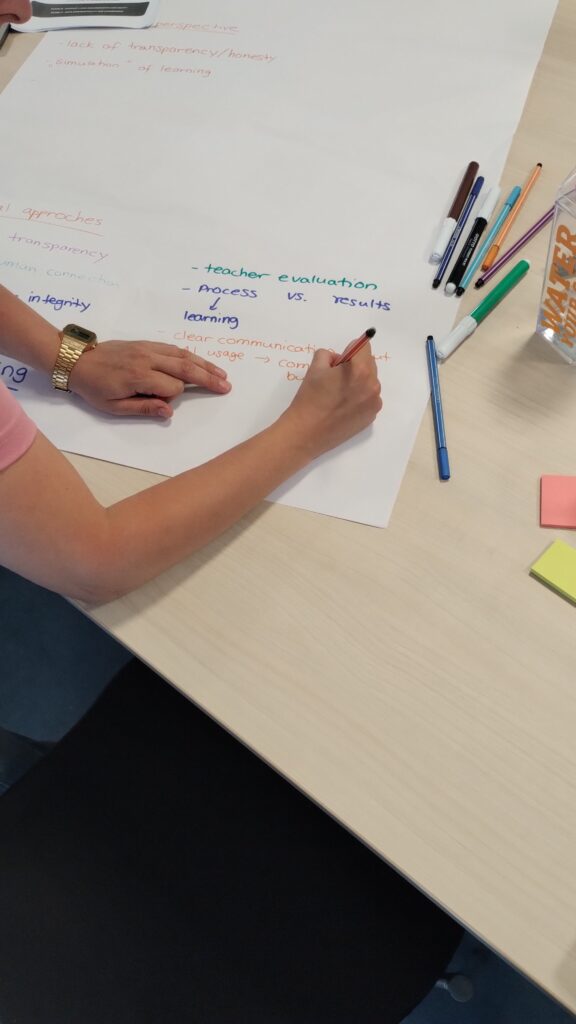

“We need to train both students and teachers”: Ethics as Practice, Not Policy

Participants converged on one practical insight: ethical AI use must be taught—but not just in a technical sense.

“It’s not just about knowing how to use it. It’s about how to think with it, or not think with it. That’s where critical training comes in.”

Another added:

“Evaluation is a big issue. If we don’t rethink assessment, we’ll just keep rewarding surface-level success.”

This led to an exploration of how educational systems—through grading structures, workloads, and funding models—shape what gets taught, what gets valued, and what gets ignored. Ethics, in this framing, couldn’t be reduced to a module or a checkbox. It had to be embedded into pedagogy, relationships, and institutional cultures.

“We can’t put everything on the shoulders of the user”: Supererogation and Systemic Responsibility

The facilitator introduced the philosophical term “moral supererogation” to describe what many participants were circling around:

“We’re asking teachers and students to be ethical… while offering them no real alternatives. That’s unfair. You can’t be a hero in a broken system.”

One participant illustrated this tension perfectly:

“I haven’t used Facebook in ten years. I don’t use WhatsApp. But when I got here, the instructor said the group is on WhatsApp. What am I supposed to do—opt out and look like a troublemaker? I got a second phone, just to fit in.”

These reflections made clear that ethical choices are rarely made in a vacuum. They are made in constrained environments, often shaped by default platforms, peer pressure, and lack of institutional support. The discussion pointed to the need for collective agreements, alternative infrastructures, and shared accountability.

“WhatsApp is easy—but at what cost?”: Platforms, Infrastructure, and Sovereignty

The group began to interrogate the technologies themselves. Why are certain tools used so pervasively in education? And what are the implications?

“We talked about WhatsApp. It’s part of Meta. And Meta pushes you to use it—it’s easy, but you don’t know what it takes to use it.”

The facilitator expanded:

“Ethics isn’t only about the human side. It’s about the ecosystem—who builds the tools, who owns the data, where the servers are. We can’t separate use from infrastructure.”

This opened up a conversation about digital sovereignty. One participant asked:

“Lucrezia is great—but it’s only for faculty. Why don’t students have access? And what happens when every university builds its own AI and server infrastructure? Who controls that?”

The ethical debate became geopolitical: energy policies, data hosting, public vs. private platforms. The boundaries between educational ethics and political economy blurred—intentionally.

“There are no checklists for this”: Ethics as Critical Inquiry and Imagination

The session closed with a call to rethink ethics itself—not as a fixed doctrine, but as a process:

“Ethics isn’t a checklist. It’s ongoing. It’s about asking, deciding, imagining… together.”

Participants spoke about building co-designed agreements with students, embedding ethics in the curriculum not as surveillance, but as dialogue.

“We could have a contract at the beginning of the course,” one educator suggested, “where we decide with students what tools we’ll use, and how.”

The facilitator echoed this direction:

“We’re in a postdigital era. Platformization, datafication, and now AI—they’re not neutral. But we can respond—not just by resisting, but by imagining different futures.”

As participants packed up, the conversation lingered—about care, about power, about what might still be possible in education. Someone joked about not having opened the good Prosecco wine offered to conclude the lunchtime. But the reflection on the ethics of AI and data had already been uncorked.

Leave a Reply